Lake Mega-Chad and the African Humid Period

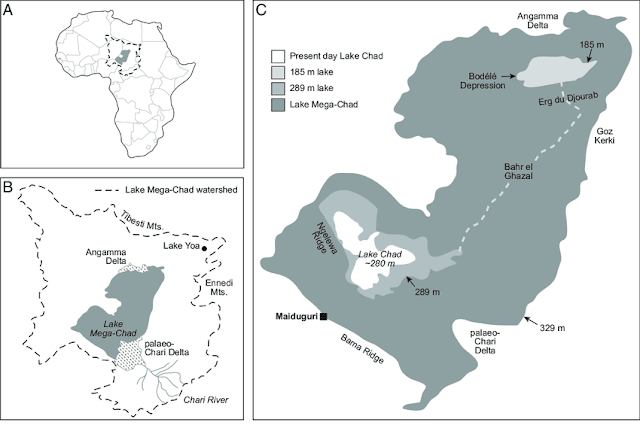

In my last post I discussed environmental change in the Lake Chad Region in comparison to that of Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa. What is even more startling than the comparison between Lake Chad and Lake Victoria is the comparison between the current extent of Lake Chad and Lake Mega-Chad (LMC). Figure 1: Location maps of Lake Chad. (B) shows Lake Mega-Chad's catchment and (C) shows the extent of present-day Lake Chad (as of 2015) compared to Lake Mega-Chad. Source: Armitage et al. 2015 The surface area of LMC is thought to have exceeded 350,000km 2 , a similar area to that of the Caspian Sea, currently the largest lake on earth ( Bouchette et al . 2010 ). LMC was the largest Quaternary body of water on the African continent. The extent of LMC is thought to have peaked around 6,000 years ago at the end of the African Humid Period. Figure 1 shows that extent of LMC compared to its basin and the current extent of Lake Chad. The African Humid Period